Introduction to Plan 9

What is Plan 9

Plan 9 is a research operating system from the same group who created UNIX at Bell Labs Computing Sciences Research Center (CSRC). It emerged in the late 1980s, and its early development coincided with continuing development of the later versions of Research UNIX. Plan 9 can be seen as an attempt to push some of the same ideas that informed unix even further into the era of networking and graphics. Rob Pike has described Plan 9 as "an argument" for simplicity and clarity, while others have described it as "UNIX, only moreso."

From The Use of Name Spaces in Plan 9:

Plan 9 argues that given a few carefully implemented abstractions it is possible to produce a small operating system that provides support for the largest systems on a variety of architectures and networks.

From the intro(1) man page:

Plan 9 is a distributed computing environment assembled from separate machines acting as terminals, CPU servers, and file servers. A user works at a terminal, running a window system on a raster display. Some windos are connected to CPU servers; the intent is that heavy computing should be done in those windows but it is also possible to compute on the terminal. A separate file server provides file storage for terminals and CPU servers alike.

The two most important ideas in Plan 9 are:

- Private namespaces (Each process constructs a unique view of the hierarchical file system)

- File interfaces (familiar from UNIX, but taken to the extreme: all resources in Plan 9 look like file systems)

Most everything else in the system falls out of these two basic ideas.

Plan 9 really pushes hard on some ideas that Unix has that haven't really been fully developed, in particular, the notion that just about everything in the system is accessible through a file. In other words, things look like an ordinary disk file. So all the devices are controlled this way by means of ASCII strings, not complicated data structures. For example, you make network calls by writing an ASCII string, not the files. This notion is something that's actually leaking quite fast.

The second thing is sort of more subtle and sort of hard to appreciate until you've actually played with it. That is that the set of files an individual program can see depends on that program itself. In a standard kind of system, either with Unix remote file systems or Windows attached file systems, all the programs running in the machine see the same thing. In Plan 9, that's adjustable per program. You can set up specialized name stations that are unique to a particular program. I mean, it's not associated with the program itself but with the process, with the execution of the process.

— Dennis Ritchie

Read: intro(1); Plan 9 from Bell Labs; Designing Plan 9, originally delivered at the UKUUG Conference in London, July 1990; and FQA 7 - System Management; for a more detailed overview of Plan 9's design.

Today, Plan 9 continues in its original form, as well as in several derivatives and forks.

The United States of Plan 9.

- Plan 9 from Bell Labs: The original Plan 9. Effectively dead, all the developers have been run out of the Labs and/or are on display at Google.

- Plan 9 from User Space: Plan 9 userspace ported/imitated for UNIX (specifically OS X).

- 9legacy: David du Colombier's cherry picked collection of patches from various people/forks to Bell Labs Plan 9. (It is not a fork.)

- 9atom: Erik Quanstrom's fork of Plan 9, maintained to Erik's needs and occasionally pilfered by 9front.

- 9front: (that's us) (we rule (we're the tunnel snakes))

- NIX: High performance cloud computing is NIX (imploded in a cloud of political acrimony and retarded bureaucratic infighting).

- NxM: A kernel for manycore systems (never spotted in the wild).

- Clive: A new operating system from Francisco J. Ballesteros, designed to generate grantwriting practice material and research projects for otherwise indolent students.

- Akaros: Akaros is an open source, GPL-licensed operating system for manycore architectures. Has no bearing on anything but has attracted grant money.

- Harvey: Harvey is an effort to get the Plan 9 code working with gcc and clang.

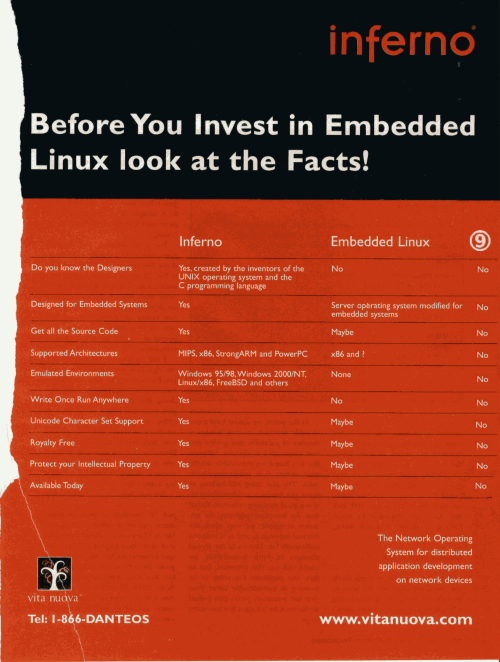

- Inferno: Inferno is a distributed operating system started at Bell Labs, but is now developed and maintained by Vita Nuova Holdings as free software. Just kidding it is not developed or maintained.

- ANTS: Advanced Namespace Tools for Plan 9. ANTS is a collection of modifications and additional software which adds new namespace manipulation capabilities to Plan 9.

- Jehanne: Jehanne:Harvey::William King Harvey:J. Edgar Hoover

- Plan 9 Foundation: Now offering downloads of historical Plan 9 releases.

Plan 9 is not UNIX

In the words of the Bell Labs Plan 9 wiki:

Plan 9 is not Unix. If you think of it as Unix, you may become frustrated when something doesn't exist or when it works differently than you expected. If you think of it as Plan 9, however, you'll find that most of it works very smoothly, and that there are some truly neat ideas that make things much cleaner than you have seen before.

Confusion is compounded by the fact that many UNIX commands exist on

Plan 9 and behave in similar ways. In fact, some of Plan 9's userland

(such as the upas

mail interface, the sam text editor, and the

rc shell) are carried over directly

from

Research UNIX 10th Edition.

Further investigation reveals that many ideas found in Plan 9 were

explored in more primitive form in the later editions of

Research UNIX.

However, Plan 9 is a completely new operating system that makes no attempt to conform to past prejudices. The point of the exercise (circa the late 1980s) was to avoid past problems and explore new territory. Plan 9 is not UNIX for a reason.

Read: UNIX to Plan 9 command translation, UNIX Style, or cat -v Considered Harmful.

Plan 9 is not plan9port

Plan 9 from User Space (also known as plan9port or p9p) is a port of many Plan 9 from Bell Labs libraries and applications to UNIX-like operating systems. Currently it has been tested on a variety of operating systems including: Linux, Mac OS X, FreeBSD, NetBSD, OpenBSD, Solaris and SunOS.

Plan9port consists of a combination of mostly unaltered Plan 9 userland utilities packaged alongside various attempts to imitate Plan 9's kernel intefaces using miscellaneous available UNIX programs and commands. Some of the imitations are more successful than others. In all, plan9port does not accurately represent the experience of using actual Plan 9, but does provide enough functionality to make some users content with running acme on their Macbooks.

It is now being slowly ported to the Go programming language.

Plan 9 is not Inferno

Inferno is a distributed operating system also created at Bell Labs, but which is now developed and maintained by Vita Nuova Holdings as free software. It employs many ideas from Plan 9 (and even shares some source code), but is a completely different OS.

Note: Inferno shares some compatible interfaces with Plan 9, including the 9P/Styx protocol.

Plan 9 is not a product

Path: utzoo!utgpu!water!watmath!clyde!bellcore!faline!thumper!ulysses!smb

From: s...@ulysses.homer.nj.att.com (Steven Bellovin)

Newsgroups: comp.unix.wizards

Subject: Re: Plan 9? (+ others)

Message-ID: <10533@ulysses.homer.nj.att.com>

Date: 23 Aug 88 16:19:40 GMT

References: <846@yunexus.UUCP> <282@umbio.MIAMI.EDU> <848@yunexus.UUCP>

Organization: AT&T Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill

Lines: 33

``Plan 9'' is not a product, and is not intended to be. It is research --

an experimental investigation into a different way of computing. The

developers started from several basic assumptions: that CPUs are very

cheap but that we don't really know how to combine them effectively; that

*good* networking is very important; that an intelligent user interface

(complete with dot-mapped display and mouse) is a Right Decision; that

existing systems with networks, mice, etc., are not the correct way to

do things, and in particular that today's workstations are not the way to

go. (No, I won't bother to explain all their reasoning; that's a long

and separate article.) Finally, the UNIX system per se is dead as a

vehicle for serious research into operating system structure; it has grown

too large, and is too constrained by 15+ years of history.

Now -- given those assumptions, they decided to throw away what we have

today and design a new system. Compatibility isn't an issue -- they are

not in the product-building business. (Nor are they in the ``let's make

another clever hack'' business.) Of course aspects of Plan 9 resemble

the UNIX system quite strongly -- is it any surprise that Pike, Thompson,

et al., think that that's a decent model to follow? But Plan 9 isn't,

and is not meant to be, a re-implementation of the UNIX system. If you

want, call it a UNIX-like system.

Will Plan 9 ever be released? I have no idea. Will it remain buried?

I hope not. Large companies do not sponsor large research organizations

just for the prestige; they hope for an (eventual) concrete return in the

form of concepts that can be made into (or incorporated into) products.

--Steve Bellovin

Disclaimer: this article is not, of course, an official statement from AT&T.

Nor is it an official statement of the reasoning behind Plan 9. I do think

it's accurate, though, and I'm sure I'll be told if I'm wrong...

Plan 9 is not for you

Let's be perfectly honest. Many features that today's "computer experts" consider to be essential to computing (JavaScript, CSS, HTML5, etc.) either did not exist when Plan 9 was abandoned, or were purposely left out of the operating system. You might find this to be an unacceptable obstacle to adopting Plan 9 into your daily workflow. If you cannot imagine a use for a computer that does not involve a web browser, Plan 9 may not be for you.

See: http://harmful.cat-v.org/software/

On the other hand, the roaring 2020s have seen Plan 9 sprout a substantial presence on social media, so if you're here for that, YMMV.

Why Plan 9?

You may ask yourself, well, how did I get here? In the words of Plan 9 contributor Russ Cox:

Why Plan 9 indeed. Isn't Plan 9 just another Unix clone? Who cares?

Plan 9 presents a consistent and easy to use interface. Once you've settled in, there are very few surprises here. After I switched to Linux from Windows 3.1, I noticed all manner of inconsistent behavior in Windows 3.1 that Linux did not have. Switching to Plan 9 from Linux highlighted just as much in Linux.

One reason Plan 9 can do this is that the Plan 9 group has had the luxury of having an entire system, so problems can be fixed and features added where they belong, rather than where they can be. For example, there is no tty driver in the kernel. The window system handles the nuances of terminal input.

If Plan 9 was just a really clean Unix clone, it might be worth using, or it might not. The neat things start happening with user-level file servers and per-process namespace. In Unix, /dev/tty refers to the current window's output device, and means different things to different processes. This is a special hack enabled by the kernel for a single file. Plan 9 provides full-blown per-process namespaces. In Plan 9 /dev/cons also refers to the current window's output device, and means different things to different processes, but the window system (or telnet daemon, or ssh daemon, or whatever) arranges this, and does the same for /dev/mouse, /dev/text (the contents of the current window), etc.

Since pieces of file tree can be provided by user-level servers, the kernel need not know about things like DOS's FAT file system or GNU/Linux's EXT2 file system or NFS, etc. Instead, user-level servers provide this functionality when desired. In Plan 9, even FTP is provided as a file server: you run ftpfs and the files on the server appear in /n/ftp.

We need not stop at physical file systems, though. Other file servers synthesize files that represent other resources. For example, upas/fs presents your mail box as a file tree at /mail/fs/mbox. This models the recursive structure of MIME messages especially well.

As another example, cdfs presents an audio or data CD as a file system, one file per track. If it's a writable CD, copying new files into the /mnt/cd/wa or /mnt/cd/wd directories does create new audio or data tracks. Want to fixate the CD as audio or data? Remove one of the directories.

Plan 9 fits well with a networked environment, files and directory trees can be imported from other machines, and all resources are files or directory trees, it's easy to share resources. Want to use a different machine's sound card? Import its /dev/audio. Want to debug processes that run on another machine? Import its /proc. Want to use a network interface on another machine? Import its /net. And so on.

Russ Cox

What do people like about Plan 9?

Descriptive testimony by long time Plan 9 users Charles Forsyth, Anthony Sorace and Geoff Collyer:

https://9p.io/wiki/plan9/what_do_people_like_about_plan_9/index.html

What do you use Plan 9 for?

Computing.

Read: How I Switched To Plan 9

See: FQA 8 - Using 9front

What do people hate about Plan 9?

John Floren provides a humorous(?) overview of a typical new user's reactions to Plan 9:

Hi! I'm new to Plan 9. I'm really excited to work with this new Linux system.

I hit some questions.

- How do I run X11?

- Where is Emacs?

- The code is weird. It doesn't look like GNU C at all. Did the people who wrote Plan 9 know about C?

- I tried to run mozilla but it did not work. How come?

Is this guy you?

Related: http://9front.org/buds.html

What is not in Plan 9

A summary of common features you may have been expecting that are missing from Plan 9:

http://c2.com/cgi/wiki?WhatIsNotInPlanNine

Why did Plan 9's creators give up on Plan 9?

All of the people who worked on Plan 9 have moved on from Bell Labs and/or no longer work on Plan 9. Various reasons have been articulated by various people.

I ran Plan 9 from Bell Labs as my day to day work environment until around 2002. By then two facts were painfully clear. First, the Internet was here to stay; and second, Plan 9 had no hope of keeping up with web browsers. Porting Mozilla to Plan 9 was far too much work, so instead I ported almost all the Plan 9 user level software to FreeBSD, Linux, and OS X.

Russ Cox (again)

The standard set up for a Plan 9 aficionado here seems to be a Mac or Linux machine running Plan 9 from User Space to get at sam, acme, and the other tools. Rob, Ken, Dave, and I use Macs as our desktop machines, but we're a bit of an exception. Most Google engineers use Linux machines, and I know of quite a few ex-Bell Labs people who are happy to be using sam or acme on those machines. My own setup is two screens. The first is a standard Mac desktop with non-Plan 9 apps and a handful of 9terms, and the second is a full-screen acme for getting work done. On Linux I do the same but the first screen is a Linux desktop running rio (formerly dhog's 8½).

More broadly, every few months I tend to get an email from someone who is happy to have just discovered that sam is still maintained and available for modern systems. A lot of the time these are people who only used sam on Unix, never on Plan 9. The plan9port.tgz file was downloaded from 2,522 unique IP addresses in 2009, which I suspect is many more than Plan 9 itself. In that sense, it's really nice to see the tools getting a much wider exposure than they used to.

I haven't logged into a real Plan 9 system in many years, but I use 9vx occasionally when I want to remind myself how a real Plan 9 tool worked. It's always nice to be back, however briefly.

Russ

Russ Cox continues:

> Can you briefly tell us why you (Russ, Rob, Ken and Dave)

> no longer use Plan9 ?

> Because of missing apps or because of missing driver for your hardware ?

> And do you still use venti ?

Operating systems and programming languages have strong network effects: it helps to use the same system that everyone around you is using. In my group at MIT, that meant FreeBSD and C++. I ran Plan 9 for the first few years I was at MIT but gave up, because the lack of a shared system made it too hard to collaborate. When I switched to FreeBSD, I ported all the Plan 9 libraries and tools so I could keep the rest of the user experience.

I still use venti, in that I still maintain the venti server that takes care of backups for my old group at MIT. It uses the plan9port venti, vbackup, and vnfs, all running on FreeBSD. The venti server itself was my last real Plan 9 installation. It's Coraid hardware, but I stripped the software and had installed my own Plan 9 kernel to run venti on it directly. But before I left MIT, the last thing I did was reinstall the machine using FreeBSD so that others could help keep it up to date.

If I wasn't interacting with anyone else it'd be nice to keep using Plan 9. But it's also nice to be able to use off the shelf software instead of reinventing wheels (9fans runs on Linux) and to have good hardware support done by other people (I can shut my laptop and it goes to sleep, and even better, when I open it again, it wakes up!). Being able to get those things and still keep most of the Plan 9 user experience by running Plan 9 from User Space is a compromise, but one that works well for me.

Russ

What Russ says is true but for me it was simpler. I used Plan 9 as my local operating system for a year or so after joining Google, but it was just too inconvenient to live on a machine without a C++ compiler, without good NFS and SSH support, and especially without a web browser. I switched to Linux but found it very buggy (the main problem was most likely a bad graphics board and/or driver, but still) and my main collaborator (Robert Griesemer) had done the ground work to get a Mac working as a primary machine inside Google, and Russ had plan9port up, so I pushed plan9port onto the Mac and have been there ever since, quite happily. Nowadays Apples are officially supported so it's become easy, workwise.

I miss a lot of what Plan 9 did for me, but the concerns at work override that.

-rob

Why did Plan 9's users give up on Plan 9?

They probably have their reasons.

Why did CIA give up on Plan 9?

What is the deal with Plan 9's weird license?

Over the years Plan 9 has been released under various licenses, to the consternation of many.

The first edition, released in 1992, was made available only to universities. The process for acquiring the software was convoluted and prone to clerical error. Many potential users had trouble obtaining it within a reasonable time frame and many complaints were voiced on the eventual Plan 9 Internet mailing list.

The second edition, released in 1995 in book-and-CD form under a relatively standard commercial license, was available via mailorder as well as through a special telephone number for a price of approximately $350 USD. It was certainly easier to acquire than the first edition, but many potential users still complained that the price was too high and that the license was too restrictive.

Richard Stallman hates the Plan Nine license (circa 2000)

In the year 2000, the third edition of Plan 9 was finally released under a custom "open source" license, the Plan 9 License. Richard Stallman was not impressed:

When I saw the announcement that the Plan Nine software had been released as "open source", I wondered whether it might be free software as well. After studying the license, my conclusion was that it is not free; the license contains several restrictions that are totally unacceptable for the Free Software Movement.

http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html

Read more here:

http://www.linuxtoday.com/developer/2000070200704OPLFSW

Theo de Raadt hates the Plan 9 license (circa 2003)

In the year 2002, the fourth edition of Plan 9 was released under the Lucent Public License. This time, Theo de Raadt was not impressed:

The new license is utterly unacceptable for use in a BSD project.

Actually, I am astounded that the OSI would declare such a license acceptable.

That is not a license which makes it free. It is a contract with consequences; let me be clear -- it is a contract with consequences that I am unwilling to accept.

Read more here:

http://9fans.net/archive/2003/06/270

Everyone hates the Plan 9 license (circa 2014)

In 2014, portions of the Plan 9 source code were again re-licensed, this time under the GPLv2, for distribution with the University of California, Berkeley's Akaros operating system. Predictably, various parties were not impressed.

Russ Cox tried to make sense of the situation by commenting in a Hacker News thread:

When you ask "why did big company X make strange choice Y regarding licensing or IP", 99 times out of 100 the answer is "lawyers". If the Plan 9 group had had its way, Plan 9 would have been released for free under a trivial MIT-like license (the one used for other pieces of code, like the one true awk) in 2003 instead of creating the Lucent Public License. Or in 2000 instead of creating the "Plan 9 License". Or in 1995 instead of as a $350 book+CD that came with a license for use by an entire "organization". Or in 1992 instead of being a limited academic release.

Thankfully I am not at Lucent anymore and am not privy to the tortured negotiations that ended up at the obviously inelegant compromise of "The University of California, Berkeley, has been authorised by Alcatel-Lucent to release all Plan 9 software previously governed by the Lucent Public License, Version 1.02 under the GNU General Public License, Version 2." But the odds are overwhelming that the one-word answer is "lawyers".

Some have suggested that confusion about licensing may have contributed to Plan 9's failure to supplant UNIX in the wider computing world.

PRAISE FOR 9FRONT'S BOLD ACTION RE: LICENSING

Any additions or changes (as recorded in Mercurial history) made by

9front are provided under the terms of the MIT License, reproduced in

the file

/lib/legal/mit,

unless otherwise indicated.

Everyone loves the Plan 9 license (circa 2021)

In 2021, the Plan 9 Foundation (aka P9F--no relation) convinced Nokia to re-license all historical editions of the Plan9 source code under the MIT Public License.

As a consequence, all of 9front is now provided under the MIT License unless otherwise indicated.

Re-read:

/lib/legal/mit

Further Reading

Plan 9 papers

Academic papers that describe the Plan 9 operating system are available here: http://doc.cat-v.org/plan_9/

Man pages

- Section (1) for general publicly accessible commands.

- Section (2) for library functions, including system calls.

- Section (3) for kernel devices (accessed via bind(1)).

- Section (4) for file services (accessed via mount).

- Section (5) for the Plan 9 file protocol.

- Section (6) for file formats.

- Section (7) for databases and database access programs.

- Section (8) for things related to administering Plan 9.

Web pages

The official website for the Plan 9 project is located at: https://9p.io/wiki/plan9

The official website for the Plan 9 Foundation is located at: http://p9f.org

The 9front fork of Plan 9 (that's us): http://9front.org

A community wiki setup by 9front users: http://wiki.a-b.xyz

Much other valuable information can be found at http://cat-v.org regarding aspects of UNIX, Plan 9, and software in general.

Books

Introduction to OS Abstractions Using Plan 9 From Bell Labs, by Francisco J Ballesteros (nemo)

Notes on the Plan 9 3rd Edition Kernel, by Francisco J Ballesteros (nemo)

The UNIX Programming Environment, by Brian W. Kernighan (bwk) and Rob Pike (rob) (this book is the most clear, concise and eloquent expression of the Unix and 'tool' philosophies to date)

9FRONT DASH 1 (the document you are reading right now, but in book form)

.bp